Simply put, a tired brain has us under‐estimate risk and be more accepting of risk.

Fatigue also has a direct effect on our physical capabilities. It reduces our muscle’s ability to generate force and decreases joint proprioception and motor performance. In layman’s terms, that means

- we feel functionally weaker (encouraging us to take more shortcuts that put us in harm’s way),

- we have impaired equilibrium and coordination (meaning poor body mechanics and material handling techniques), and

- we lose our sense of balance (more slips, trips and falls).2

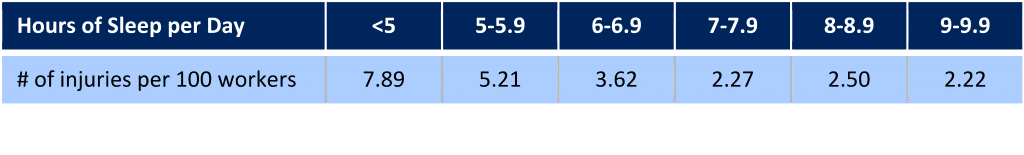

Sleep Debt and Injuries

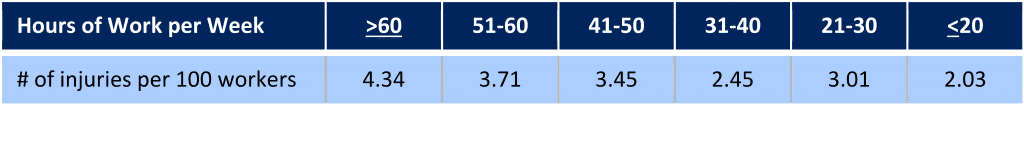

All of this translates into more injuries that are preventable, and we have the research that backs this. For example, in a study of 11,000 Americans over a 13‐year period, jobs with overtime schedules had a 61% higher injury risk rate compared to jobs without overtime.3 The same study also found that working at least 12 hours per day was associated with a 37% increase in relative risk and working at least 60 hours per week was associated with a 23% increase. In 2010, researchers examined four years of data and were able to demonstrate the impact of sleep and working hours with the relative risk for having a work‐related injury.4

Are your people at risk?

Science reveals there are four key fatigue factors that influence our risk for injury.

- Long work hours

- Irregular schedules

- Short sleep duration

- Poor sleep quality

What to do?

Productions still need to focus on reducing physical fatigue to reduce injury risk. That includes

- Incorporating material handling aids, like exoskeletons

- Suspending tools with jigs, vices, winches, tool balancers

- Job rotation to distribute heavy or repetitive work

- Longer or more frequent breaks for demanding work or challenging environments

Risk associated with sleep‐related fatigue can be addressed by

- Incorporating schedules that accommodate for adequate recuperative sleep (consider commute times and their impact)

- On duty rest breaks in quiet areas

- Ensuring good housekeeping to reduce hazards that may go unnoticed when tired

- Improving lighting in darkened areas

- Increases in cross‐checking and double‐checking

- Incorporation of checklists to reduce errors and incidents

- Ensuring fatigued workers have safe transport home

Ultimately, preventing injuries requires multiple, overlapping ergonomic controls that address both physical and cognitive factors.

1 Abd‐Elfattah, H., Abdelazeim, F., & Elshennawy, S. (2015). Physical and cognitive consequences of fatigue: A review. Journal Of Advanced Research(3), 351‐358. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2015.01.011

2 Dembe AE, Erickson JB, Delbos RG, et al. (2005).The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: new evidence from the United States. Occup Environ Med 62:588–597.

3 van der Linden, D. (2011). The urge to stop: The cognitive and biological nature of acute mental fatigue. American Psychological Association.

4 Lombardi DA, Folkard S, Willetts JL, Smith GS. Daily sleep, weekly working hours, and risk of work‐related injury: US National Health Interview Survey (2004‐2008). Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1013‐1030.